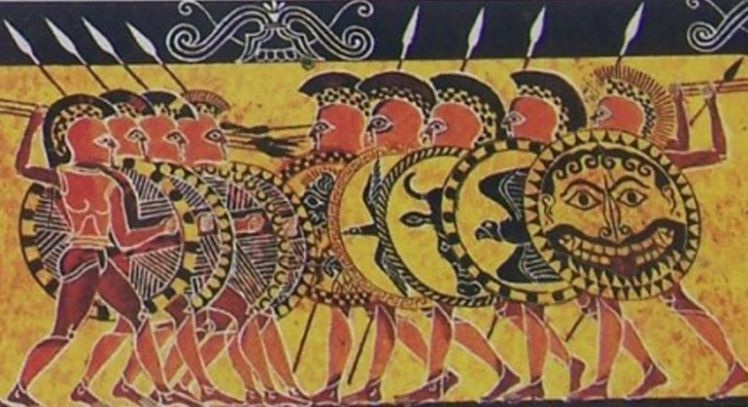

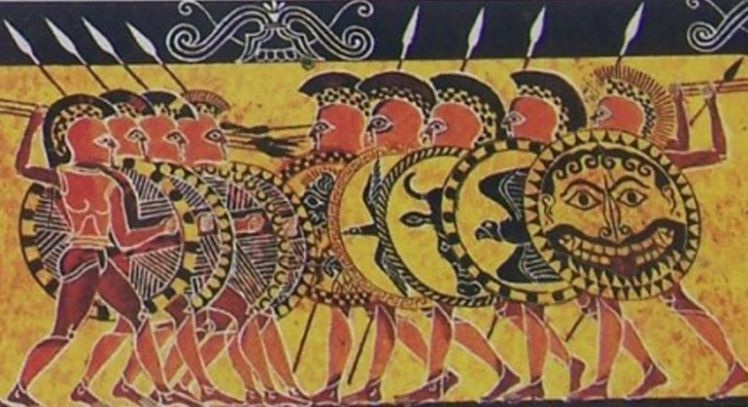

The Teaching Guide has 8 questions on Chapter 1, “Greeks and Macedonians: Poetry, Philosophy, and the Phalanx.” Question 7 asks, “Can we imagine what it would have been like to train as a hoplite, to exercise leadership as a Greek commander, to fight in a phalanx?” I sometimes refer to this type of question as a “time machine.” The past is a very strange place, and the remote past may be almost unknowable, but perhaps we can, by an effort of imagination and empathy, by stressing the human essentials, make at least an honorable effort at understanding history as it was experienced by those who lived it.

The Teaching Guide has 8 questions on Chapter 1, “Greeks and Macedonians: Poetry, Philosophy, and the Phalanx.” Question 7 asks, “Can we imagine what it would have been like to train as a hoplite, to exercise leadership as a Greek commander, to fight in a phalanx?” I sometimes refer to this type of question as a “time machine.” The past is a very strange place, and the remote past may be almost unknowable, but perhaps we can, by an effort of imagination and empathy, by stressing the human essentials, make at least an honorable effort at understanding history as it was experienced by those who lived it.

When asking a time machine question, I encourage students to use what may be like experiences to approach the subject. In this case, an experience of contact sports, military drill in formation, of any highly taxing physical effort may help us to get closer. If the sport involved the wearing of protective equipment, so much the better. Of course, if any students are veterans, this can give them a special insight. I recall the part of Bill Mauldin’s WWII memoir, Up Front in which he tries to describe the experience of the infantryman to a civilian. Fill a suitcase with rocks; walk around the neighborhood with it all day; come home and dig a hole in your backyard; stay in it all night, trying to stay awake with thoughts that someone is going to come out of the darkness, beat you over the head, attack your family and rob your house (etc.) Across the years and even the centuries, the experience of fear and fatigue, of trying to stay on top of a situation getting out of control, of acting both in unison and as an individual in a rough and dirty game, have not changed to be unrecognizable. Next time you march in formation, imagine at the end of the march you’ll be launched into a deadly, hand-to-hand fight. Imagine your worst football, rugby, hockey, or lacrosse game. OK, imagine 10 times rougher, the stakes much higher, friends who never walk off the field.

Away from the classroom, the reading of history and literature can have an influence on how military life is experienced. The sand berms, body armor and helmets, even our location in the land of the Tigris and Euphrates constantly reminded me of the Roman Legions when I was in Iraq, so that I named my OIF-1 monograph “Desert Legion.” Even more vivid and lasting were my thoughts of Homer’s “wine dark sea” one time flying over the Mediterranean in a CH-53. On this occasion, I was flying back to my own vessel the Bataan leaving the task force flag ship Kearsarge. This was 2003. We were headed to Kuwait and Iraq. I’d gone to the Kearsarge to get some interviews I needed in my role as field historian. The Marine task force operations officer, a Basic School classmate, had done me the honor of briefing me on the tentative plan of attack and asking for for comments. On the flight back, I had the thought that, yes, we were going to do this: we’re going to invade Iraq, one way or another. Then I had my Homer moment. The aircraft banked and I caught a glimpse of the dark sea over the rear ramp. I thought of all the fighting ships and men who had passed this way: Homer’s (or Helen’s) 1,000 ships, galleys and galleons, men of war, dreadnoughts, escorts and merchantmen in convoy. My part had been written long ago, and all I needed to do was play that part. The worse things got, the more I might be needed, to help and encourage, as long as I remained standing. These thoughts stayed with me the rest of the campaign.

Maybe the best way to get inside the head of a Greek hoplite is to read Homer and some of the Greek plays that deal with war, like Sophocles’s Ajax. That was what they carried in their heads on the way to battle, along with thoughts of home and family, the fight ahead, their own chances of victory and survival, as have soldiers in every age.

It looks like I’ll be doing a book signing and sale for Soldiers and Civilization at the U.S. Merchant Marine Academy Navy Exchange (NEX) on 1 September. Copies of the book will be available for sale and signing, and of course those who already own copies are invited to stop by to get them signed and maybe for a chat. The NEX is in the underground passageway referred to as “zero deck.” This area is open to Academy visitors. Hours planned are 0730-1630.

It looks like I’ll be doing a book signing and sale for Soldiers and Civilization at the U.S. Merchant Marine Academy Navy Exchange (NEX) on 1 September. Copies of the book will be available for sale and signing, and of course those who already own copies are invited to stop by to get them signed and maybe for a chat. The NEX is in the underground passageway referred to as “zero deck.” This area is open to Academy visitors. Hours planned are 0730-1630.